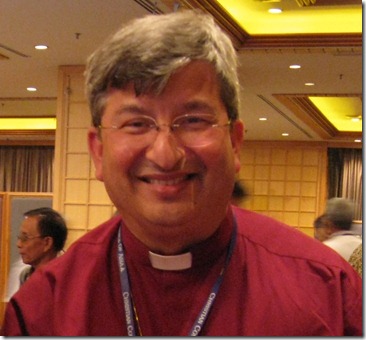

“CALLED TO PROPHESY, RECONCILE AND HEAL”

A sermon by the Most Reverend Roger Herft Archbishop of Perth

Wednesday, 15 April 2010 13th CCA General Assembly Opening Worship

Ezekiel 37:1-10 I prophesied as he commanded me, and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood on their feet, a vast multitude (vs 10).

The Easter Anthem

2 Corinthians 5:14-21 That is, in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting the message of reconciliation to us (vs 19).

St Mark 16:1-8 So they went out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid (vs 8).

God of holy dreaming, Great Creator Spirit,

from the dawn of creation you have given your children

the good things of Mother Earth.

You spoke and the gum tree grew.

In the vast desert and dense forest,

and in cities at the water’s edge,

creation sings your praise.

Your presence endures

as the rock at the heart of our Land.

When Jesus hung on the tree

you heard the cries of all your people

and became one with your wounded ones:

the convicts, the hunted, and the dispossessed.

The sunrise of your Son coloured the earth anew,

and bathed it in glorious hope.

In Jesus we have been reconciled to you,

to each other and to your whole creation.

Lead us on, Great Spirit,

as we gather from the four corners of the earth;

enable us to walk together in trust

from the hurt and shame of the past

into the full day which has dawned in Jesus Christ. Amen.

A Prayer Book for Australia, Broughton Books, Victoria, 1999

| Ko te Karaiti te hepara pai, e mohio ana, e atawhai ana i nga hipi katoa o ia kahui. I roto i a te Karaiti, kahore he tangata whenua, kahore he tauiwi, Kahore ano hoki he tau-arai. I roto i a te Karaiti, ka tohungia te rawakore, ka hunaia te pono i te hunga kawe mohio, ka whakaaturia ki te hunga ngakau papaku. | Christ is the good shepherd who knows and cares for every one of the sheep in different folds. In Christ there is neither Jew nor Gentile; in Christ there is no discrimination of gender, class or race. In Christ the poor are blessed, the simple receive truth hidden from the wise. |

| Areruia! Kororia ki te Atua o te tika, o te aroha, Nau i toha nga mahi ma matou, I rumakina ai matou ki te mamaetanga, puea ake ana ki nga hua o te aranga. Pupu ake i a koe te mana atawhai, kia ai ta matou atawhai i etahi atu, kia mau ai te rongo ki te hunga katoa e manawa pa ana, ki tau nei ao. | Alleluia! God of justice and compassion, You give us a work to do and a baptism of suffering and resurrection. From you comes power to give to others the care we have ourselves received so that we, and all who love your world, may live in harmony and trust. New Zealand Prayer, He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa, Collins Publishers, Auckland, 1989, p478 |

Invocation to the Holy Spirit in Sinhala and Tamil.

I greet you in the name of the Holy and Blessed Trinity; Father, Son and Holy Spirit; God the Creator, Redeemer and Giver of Life in whom and through whom we are called to prophesy, reconcile and heal.

I was born and lived most of my life in Sri Lanka. The call to worship from temple, mosque, kovil and church form an essential part of my sound bank. Many of the religious traditions that are so evident in Asia nourished the community that shaped me into adulthood. I share their profound aspirations for peace, compassion, mercy and love for all creation. As a Christian I try to engage with their radical yet different views concerning ultimate reality in an attitude called for by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks of “living with the dignity of difference”. I am saddened that religious people captive to diabolical forces continue in the name of God to bring division, conflict, persecution and death to many peoples in Asia and across the world.

I stand as an in-between half caste, a living expression of the colonial leftovers – a mixture of the Portuguese, Dutch and British invasions. I am inextricably linked to the major races, Sinhalese and Tamil through marriage and family ties that form a part of who I am.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s definition of the human being through the African word ‘Ubuntu’ is one that I find helpful. I, as an individual, do not exist in any meaningful way – I am because you are. My identity receives its integrity when I become deeply aware of the you before and around me, be they friend, family, stranger or foe.

In the Christian tradition my inheritance has an ecumenical flavour; baptised by an English missionary, I was confirmed by Bishop Lakshman Wickremesinghe, a visionary leader whose memory is cherished in the CCA. My father’s faith allegiance caused me to be attentive to the Methodist Church with stalwarts like Dr D T Niles, one of the most significant contributors to the ecumenical movement and a founder of the CCA.

In school and seminary I was influenced by Roman Catholic Bishops of prophetic zeal, Baptists, Churches of Christ, Presbyterian, Pentecostals, Orthodox, liberals and the in-betweens. The many strands of Reformed and Catholic theology and practise held in dynamic tension in the Anglican Communion is the world that I inhabit. Scottish theologian Dr Elizabeth Templeton describes Anglicans eloquently in her courageous intervention at the Lambeth Conference of Bishops in 1988:

Both internally and in relation to other evolving Christian life-forms, you have been conspicuously unclassifiable, a kind of ecclesiastical duck-billed platypus, robustly mammal and vigorously egg-laying. That, I am sure, is to be celebrated and not deplored.

Elizabeth Templeton, Appendix 4, The Truth Shall Make You Free, The Lambeth Conference 1988, Anglican Consultative Council, London, 1988, p292

The Marxist socialist element present in Sri Lanka’s history was not to be lost to me as my family had links with leaders in society and the church who were renowned for their strong Communist ideals. On hearing of my desire to be a priest, one of my uncles remarked that he did not wish to have a clerico fascist in the family!

I am conscious that I stand here today on the shoulders of giants. Those women and men who through their faithfulness to the Gospel have shaped me in ways that I can hardly comprehend. All I can do is to give thanks and praise to God for them and for movements like the CCA that continue to shape Christian leadership in the servant mould of Christ (Philippians 2:5-11).

I do not stand here alone. I am surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses. Those from my childhood, adolescence and early adult life in Sri Lanka who shaped me in my formation as a human being and as a Christian. The elders of both Maori and Pakeha in Aotearoa New Zealand who challenged my comfortable church zones and who continue to disturb me when I settle into patriarchal captivity or a comfortable church culture. The Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander leaders and communities and the many elders in the Australian community who constantly remind me that faith has twin sisters – “anger at the way things are and hope that change can happen” (St Augustine).

I am also deeply conscious of the members of the L’Arche Community across the world, those beloved of God who in their disability, pain and vulnerability have given me a deeper vision of what it is to be a Christian, a human being called to follow the Christ of Galilee, the prophet, reconciler and healer. Jean Vanier, the founder of L’Arche, reminds us that Christ comes to us through the weak, poor, the dispossessed, the physically and mentally disabled. We are not there to offer to them acts of charity in the form of patronising welfare. In mutual encounter we discover the face of Christ and recognise our common woundedness caused by rejection and dislocation. We receive healing through the prophetic word and action that awakens and reconciles us, calling us to be “wounded healers”.

In the next few minutes you may wish to spend some time in silence and then speak to your neighbour and exchange a memory of a person, a moment that shaped and continues to shape you as a person.

What does it mean for church and individuals to be called to prophesy, reconcile and heal? How may the Holy Scriptures read to us today point us through the Living Word of God to gain an understanding of how we may in Christ be prophets, reconcilers and healers?

Ezekiel the prophet, whose name means ‘God strengthens’, lived in a particularly challenging context in the history of the people of Israel.

The so-called unified kingdom of David and Solomon, much the envy of the ancient world, had been divided into the North and the South. In 721BC the Assyrian powers took control of the North and in 587BC the Babylonians occupied the South. The strategy deployed by the Great Empires to destroy a nation’s hopes and aspirations was to forcibly move people out of their land. Buildings, houses and places that gave meaning and purpose were destroyed adding to the desolation of an already vanquished people. The poor, the weak, the so-called rabble were left behind to eke out an existence amongst the ruins.

Ezekiel is in a displaced persons’ camp, a refugee in Tel Abib. Here he receives his call to be a prophet. He is overwhelmed by the context and experiences a profound sense of grief. The death of his wife adds to his lament. He cannot even mourn for her with the customary rituals associated with the death of a loved one. He uses his experience of anguish and lament to proclaim in word and symbol God’s activity in bringing about the fall of Jerusalem. He shocks the people by suggesting that the presence of the Sanctuary of God will be discovered in exile. His message is shaped by the pain and rebellion of the people and journeys from judgement, to calls for repentance, to salvation and healing.

The call Ezekiel receives comes as a surprise. He is caught up in a vision of God’s action and movement, fluttering wings and whirring chariot wheels – symbolic expressions of God’s sovereign power. The sounds of hope in the birds’ wings interact with the jarring instruments of war. To be called to prophesy is to never let go of the vision of God – God’s sovereign power over all creation, over all time, over all ages. The call to prophesy can only arise, be nourished and nurtured in an atmosphere of prayerful discernment.

Prayer awakens the soul, opens the eyes of the heart and gives space for a vision of God beyond our imaginings. Dr D T Niles, in his significant theological reflection on Christian mission, takes cognizance of God’s ultimate reign over every aspect of the world:

The Christian message is not addressed to other religions, it is not about other religions: the Christian message is about the world. It tells the world a truth about itself – God loved it and loves it still; and, in telling that truth, the Gospel bears witness to a relation between itself and the world.

. . . the world is non-Christian only in a temporal and, in fact, a temporary sense (Rev.11:15). It is already in God’s purpose a world for which Jesus died and over which He rules (Matt.28:18).

D T Niles, Upon the Earth, p235

The State of Western Australia is blessed by the memory of a pioneer saint who saw God at work in the ancient continent of Australia long before any Christian missionary set foot on the land. In his Journal of 1842 he wrote:

The view on such occasions was cheerless, depressing & almost awful, not a living creature to be seen. – the sky glowing with a misty fervent heat, & the deep silence unbroken by the slightest sounds.

In that which I have seen – generally speaking – the absence of animal life, the want of verdure & the terrible effects of fire, render it melancholy and distressing. – I did not experience that effect upon the mind which is caused by the magnificent or sublimity of Nature, yet, notwithstanding, I must own I felt the truth of the lines;

“Midst Forest Shades, and silent Plains,”

Where Man has never trod;”

There in Majestic power He reigns,”

The ever-present GOD!”

Geoffrey Bolton, Heather Vose and Genelle Jones (Eds), The Wollaston Journals, Volume 1,

University of Western Australia Press, 1991, p187

To be called to prophesy is to take time to pray in joyful praise and in deep pondering. Prayer makes us humble and reminds us that God travels ahead of us and that the world is in God’s hands. Ezekiel’s vision of God’s sovereignty comes from being overwhelmed with the pain and suffering of the people in exile.

Then the spirit lifted me up, and as the glory of the Lord rose from its place, I heard behind me the sound of loud rumbling; it was the sound of the wings of the living creatures brushing against one another, and the sound of the wheels beside them, that sounded like a loud rumbling. The spirit lifted me up and bore me away; I went in bitterness in the heat of my spirit, the hand of the Lord being strong upon me. I came to the exiles at Tel-abib, who lived by the river Chebar. And I sat there among them, stunned, for seven days. At the end of seven days, the word of the Lord came to me: Mortal, I have made you a sentinel for the house of Israel; whenever you hear a word from my mouth, you shall give them warning from me.

Ezekiel 3:12-17

I remember as a part of my theological training living in a slum in the heart of Colombo. Most of the people lived on the street. The tin shed that I was given hospitality in had six adults, three children, two babies feeding at their mother’s breasts, and a goat hung from a make-shift beam. The local Buddhist temple, mosque, church and kovil were arguing about the naming of the street. Fierce debate raged about which religious tradition would receive the naming rights for this street in a slum that held within it the poorest of the poor!!

How easily can the prayerful lose perspective? Tagore’s call for religions to bear the integrity of dust come to mind:

Leave This

Leave this chanting and singing and telling of beads!

Whom dost thou worship in this lonely dark corner of a temple with doors all shut?

Open thine eyes and see thy God is not before thee!

He is there where the tiller is tilling the hard ground

and where the pathmaker is breaking stones.He is with them in sun and in shower,

and his garment is covered with dust.

Put off thy holy mantle and even like him come down on the dusty soil!Deliverance?

Where is this deliverance to be found?

Our master himself has joyfully taken upon him the bonds of creation;

he is bound with us all for ever.

Come out of thy meditations and leave aside thy flowers and incense!

What harm is there if thy clothes become tattered and stained?

Meet him and stand by him in toil and in sweat of thy brow.Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941)

Ezekiel finds himself standing in a valley of dry bones, the place of death, of despair and hopelessness. Whether this was in Babylon, the place of exile, or in Jerusalem, the city that was left in ruins, we do not know. All we do know is that it is a place in which there is little or no hope of life. Grief overwhelms him at the sight of such horrible devastation. He recognises yet again that the call to prophesy can only take place when we learn to grieve, to lament and to mourn with prayerful attentiveness to “what is”.

Tears are a way of solidarity in pain when no other form of solidarity remains . . . This tradition of biblical faith knows that anguish is the door to historical existence, that embrace of ending permits beginnings.

Walter Brueggemann, The Prophetic Imagination, Fortress Press, USA, 1978, pp59-60

It is good to ask ourselves what is it that causes us to deeply groan and grieve. One of my most poignant memories is as an eight year old travelling with my mother to the bakery. Racial riots had broken out; gangs were moving down the street in search of people from a minority race. They grabbed a person hiding in a nearby shop. The roads were being tarred and there were barrels of boiling tar ready to be put on the gravel path. They lifted this man and put him into the boiling liquid. The terror in his eyes and his screams mingled with the brutality and callousness of his murderers remain with me to this day, as does the silence of those of us who became paralysed spectators to this snuffing out of life.

I deeply grieve the ways in which we humans act with such hatred and bitterness towards one another.

As Christians in Asia we who seek the call to prophesy must first ask God to gift us with tears that wash our eyes and burn our hearts to see the suffering and pain of the world in which God has placed us. The tears of Jesus, the living, pulsating Word of God, come from an anguished heart. A heart that refuses to let dry bones have the last word. God’s living word of hope bursts forth as the breath of God inspires the dry bones to rattle, to shake, to grow sinew, muscle and flesh and to take life. The Word that called creation into being brings new life to bear – it heals and reconciles, even as it brings the prophetic vision to bear.

I prophesied as he commanded me, and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood on their feet, a vast multitude.

Ezekiel 37:10

The call to prophesy, reconcile and heal is addressed to the church. In the Corinthian correspondence the apostle Paul is at pains to remind the various parties, factions and groups in the church that they are called to be a community growing in reconciliation.

Still steeped in their old Corinthian ways they judged others not on the things that mattered but on superficial, outward appearances. They prided themselves in status and used their newfound place in the Christian church to look down upon those who were not endowed with one gift of the Spirit or another. They failed to see that the greatest gift of God to them in the death and resurrection of Jesus was not theirs to possess or monopolise.

But we have this treasure in clay jars, so that it may be made clear that this extraordinary power belongs to God and does not come from us.

2 Corinthians 4:7

Paul challenges them to be the “new creation” they are called to be and become in Christ. God has initiated the primary act of reconciliation on the cross. The sinless Son of God has become Sin in order that we may become the righteousness of God. The church exists to be the reconciled community of God and to be ambassadors of this reconciliation to those within the household of faith and to those to whom the church is called to bear witness of God’s reconciliation to the world.

In defence of what Leslie Newbiggin called the ‘scandal of denominationalism’, it is argued that the growing variety of churches we have today is an expression of God-given diversity, a tangible revelation of what it means to be the “Rainbow People of God”. The sad and sinful reality is that our history is one of competition and rivalry in which we refuse to see in each other the image of God. We rightly critique the Colonial powers for their exploitation of our peoples, yet continue to live by the labels placed upon us by those who brought the Gospel into our midst. We use consumer choice and capitalist marketing and competitive mechanisms to peddle our particular Christian brand to the world, often engaging in propaganda that diminishes and belittles others who claim the name of Christ. Indian Saint Sadhu Sundar Singh observed that Christians worship the pot in which the Gospel came to India rather than the plant. We fight about which pot is better and brighter and forget how damaging this sinful madness is to our witness to the life-giving, radical, transforming Gospel – to the Saviour who prayed for our unity in Him and with each other “so that the world may believe”.

Elizabeth Templeton’s call for us to be the reconciled community in Christ makes challenging reading:

My first conviction is that there are no outsiders, or that all ‘outsiderness’ is to be regarded as provisional, since God’s lively and inviting love is without bounds. The Church exists to represent, cradle and anticipate the future of all our humanness, which is hidden, with the healing of creation, in the love and freedom of God.

Any unity we seek must be to enact and articulate that. It cannot then be the unity of a strong and exclusive club, which makes the outsider more outside, more alien, more at bay. . . It is not a separate enclave, not separable. As Hooker so gently puts it in his ‘Sermon on Pride’:

God hath created nothing simply for itself: but each thing in all things, and of everything each part in each other have such interest, that in the whole world nothing is found whereunto any thing created can say, ‘I need thee not’.

Her comments remind us of the metaphor of the body used in 1 Corinthians 12 and in the breaking of walls that divide in Ephesians 2:14f. Templeton warns those of us committed to the ecumenical journey that:

Outsiders, too, are properly sceptical about much of our inter-Church activity, recognising in it, better than we may ourselves, the permanent lure of a Superchurch, corresponding to the Superman God of much popular religious longing, and created in his image for our exclusive self-preservation.

This Superchurch tempts many in all our Churches, offering instant relief from panic, from the pain of facing the complexity of life, and the diversity of human responses to it. It even tempts some in the world, battered as they are by the threat of nuclear winter, sexual catastrophe, economic disaster and ideological impasse.

Templeton puts her finger on the throbbing pain of our deepest division, that dislocation which haunts Christianity and permeates all faiths and ideologies.

. . . the hardest underlying polarity in all our interdenominational and intradenominational battles is that there are among us those who believe that the invincibility of God’s love discloses itself in some kind of absolute, safeguarded articulation, whether of Scripture, Church, tradition, clerical line-management, agreed reason, charismatic gifts, orthopraxis – or any combination of such elements. And there are those among us who believe that the invincibility of God’s love discloses itself in the relativity and risk of all doctrine, exegesis, ethics, piety and ecclesiastical structure, which are the Church’s serious exploratory play, and which exist at an unspecifiable distance from the face to face truth of God. What unity is possible in concrete existence between those on either side of the trans-denominational divide seems to me our toughest ecumenical question. If we can find a way through that one, I suspect that all our specific problems of doctrine, ministry and authority will come away as easily as afterbirth. But if we seek in any of our bilateral or multilateral shifts to mask, suppress or smother that divide, our so-called unity will be a disastrous untruth.

Elizabeth Templeton, Appendix 4, The Truth Shall Make You Free, The Lambeth Conference 1988,

Anglican Consultative Council, London, 1988, pp289-91

To be called to reconcile is to take these polarities seriously, to refuse to demonise the other and to grieve at our divisions. May our Christian traditions, wherever they are on the scale of the faith map, be gifted with the magnanimity spoken of by the prophet Isaiah:

Enlarge the site of your tent, and let the curtains of your habitations be stretched out; do not hold back; lengthen your cords.

Isaiah 54:2

To see Christ in the eyes of other Christians is to be gifted to see Christ in all and to conduct the mission of the church with humility and grace.

The confession is ‘Christ in you the hope of glory’; this is the secret hidden in past times, and now to be made known in the midst of Asian life and history. Christ is incognito within us who know and acknowledge Him, but is in each and all, as the hope of life glorified and divinised, by surrender to the Father’s will, and by lowly service to all who are His children. This is the way, the life and the truth. As we share the way and the life, we make known the truth to our neighbours and fellow-wayfarers, about Christ Jesus. Whom He calls He will make His disciples, and lead to baptism and sharing in the breaking of bread, and in the apostolic fellowship. Our duty is to testify, but who accepts that testimony is the work of His free and sovereign grace. As Dr T Niles says:

Cognito and incognito

and never the one without the other

He comes constantly challenging discovery.

To discover Him

Is to discover God and neighbour too.

Lakshman Wickremesinghe, “Living in Christ With People”, A Call to Vulnerable Discipleship,

CCA Seventh Assembly, 1981, p45

The Jesus event is a breathtaking risk that God takes to be Immanuel. And the risk continues as we are called to be that “living body” in the world.

Reconciliation is then more than us living happily together. It is the invitation we are given to be the “sign” and witness of the costly unity found in the very essence of God, the Holy and Blessed Trinity.

It calls us to be healers, whose motivation comes from the One who was broken, wounded, forsaken and whose dying and rising offers the world the forgiveness that heals.

St Mark’s Gospel places the cross at the centre of the Christian message and in a strange and unexpected way leaves the resurrection as an open-ended healing event.

We are left with the disciples outside the tomb on that first Easter morning in a shocked state. They are not sure what to witness to.

The had watched Good Friday unfold. They experienced darkness and despair as Jesus is crucified. In the space of 24 hours the “hands that rocked the universe into being” are nailed to a cross. Muslim novelist Kamel Hussein of Egypt reflecting on Good Friday in his book City of Wrong notes:

‘The day was Friday. But it was quite like any other day. It was a day when men went grievously astray. Evil overwhelmed them and they were blind to the truth . . . They were caught in a vortex of seducing factors . . . They did not realize that when men suffer the loss of conscience there is nothing that can replace it. When humanity has no conscience to guide it every virtue collapses, every good turns to evil and all intelligence is crazed. On that day men willed to murder their conscience and that decision constitutes the supreme tragedy of humanity. The events of that day do not simply belong to the annals of the early centuries. They are disasters renewed daily in the life of every individual.”

Quoted by John V Taylor, Weep not for me

St Mark’s resurrection narrative begins with ‘When the Sabbath was over’. Good Friday does not move directly to Easter Day. There is a pause in the story as the body of Jesus is laid in the tomb. The ritual of embalming and anointing cannot take place as the Sabbath comes upon them. Remember Ezekiel who had no time to provide for the rituals of mourning for his wife.

The prophet Ezekiel and the apostle Paul in his Letters to the Corinthians remind us that to be called to prophesy and to reconcile we must know what it is to grieve. To be called to heal we must experience the confusion that comes with seeking the causes that bring about illness, brokenness, disease, the demonic within individuals and society. The creation in its groaning birth pangs awaits a new dawn to arise with “healing in its wings”. Our wanton waste of natural resources, the pollution of the earth, the degradation of the environment, our repeated abuse of this fragile planet has finally caught our attention. Little comfort that Asian theologians like Dr M M Thomas almost 60 years ago heard the “death rattle”. He warned that blatant consumerism and greed would fatally disturb the sensitive equilibrium of the earth and threaten the sustainability of our environment.

The death of Jesus and his burial brought forth the grief of creation – darkness, clouds, earthquakes and a sign in the temple that the God imprisoned in a sanctuary had sanctified the whole of creation. The day set aside in the Jewish tradition to remember restfulness in God’s goodness, the Sabbath, proves to be a Holy Saturday – a pause for repentance, a time of regret, to take stock of the unfulfilled hopes and shattered dreams for humanity and the whole of creation.

To be healers in our world is to know what it is to live in such a Sabbath time. Words written in response to a service held in the cemetery of Bergen-Belsen, the Nazi concentration camp where many died of starvation and illness even after the camp was liberated, is provocative in its questions:

To look at the promised land from afar and not set foot on its soil.

To dream of milk and honey and not to taste the mixture.

This was the lot of Israel’s greatest prophet.

There are many prophets in the wilderness, who die outside the promised Land.

Squeezed between Good Friday and Easter,

ignored by preachers and painters and poets,

Saturday lies cold and dark and silent

an unbearable pause between death and life.

There are many Saturday people to whom Easter does not come.

There are no angels to roll the stones away.

There are many Saturday people in the world today;

children dying of want, of food and affection,

brides who bring little or no dowry,

mothers who break stones and carry bricks,

boat people waiting for the end of the right to asylum debate,

prisoners who die in custody and those killed while trying to escape,

hostages who do not see the light of day

and detainees who do not see a courtroom,

tribes evicted from forests and fisher folk separated from the sea,

generations without nations and peoples and tribes doomed to die without hope.

The prophets who lead the Saturday people

die with them outside the promised land.

There is a cross in every Resurrection.

Is there a Resurrection in every Cross?”

John Carden, A Procession of Prayers, pp285-86

To be called to be healers means that we grieve with Saturday people, with the created and with creation. With all who live in a Good Friday world unable to hear or to join in the Alleluias of Easter.

The Gospel of St Mark ends with the word “Gar” which means “for”. It stops halfway through a sentence that speaks of fear and amazement. The reason why the Gospel ends in this way has been and is the subject of great debate - was the original torn in the travels, was Mark forced to stop halfway through a sentence as the authorities surrounded the place in which he was writing? We will never know. One group of scholars suggest that the writer has deliberately left the sentence suspended, pointing to the truth that while Jesus is raised from the dead and goes before the disciples, each disciple must accept his risen presence and move from the death on Good Friday, through the waiting of the Sabbath to a place of new beginnings.

One of the pectoral crosses I wear is a gift from the Sri Lanka Diaspora in Auckland, Aotearoa, New Zealand. Many of the families had their houses burned during racial riots. Others have faced personal tragedy as a consequence of the battles, both from the Tiger movement and from the military. The cross is one associated with Sri Lanka’s early Christian traders, it depicts the cross rising in the midst of a lotus blooming in a dark pond. In giving it to me the senior elder of the Sri Lankan community, Tom Navaratnam, prayed that I would be a healer. Christ has broken all the cycles of violence we perpetrate on humanity and on the fragile earth we inhabit. Christians are called as forgiven sinners to live with prophetic zeal and reconciling love.

The other is from the Tainui Maori community. Bishop Manu Bennett placed it on my head. He observed that he had faced racial tension in the church and in the wider community. In the Hongi, the touching of our noses, he reminded me that the breath that I breathe and the breath that he breathed came from the same source. The cross a symbol of God’s breath offered fully to the world. He invited me to live in the breath of God, for God alone is the source of our call to prophesy, reconcile and heal.

As we journey into this Assembly may we receive the breath of God, with awe, reverence, repentance and prayer and may we be Blessed in the words attributed to St Francis of Assisi:

May God bless you with discomfort,

at easy answers, half-truths, and superficial relationships,

that you may live deep within your heart. Amen.

May God bless you with anger,

at injustice, oppression, and exploitation,

that you may work for justice, freedom, and peace. Amen.

God bless you with tears,

to shed for those who suffer pain,

rejection, starvation, and war,

that you may reach out your hand to comfort them

and turn their pain to joy. Amen.

May God bless you with foolishness,

to believe that you can make a difference,

that you may do what others claim cannot be done. Amen.

And the blessing of the Holy and Life-Giving Trinity,

Father, Son, and Holy Spirit,

be with you now and always. Amen.

The Most Reverend Roger Herft

Archbishop

April 2010

No comments:

Post a Comment